Interviewing the creator of The Crimson Diamond

Before we get started I just wanted to say that The Crimson Diamond has been a very interesting experience as a first time Text Parser Adventure, and it was absolutely wonderful. So, thank you for that!

Julia: Oh, thank you! I love hearing from people who have never played a text parser before. I always expected my primary audience to be people who fondly remember the old stuff, but I’m most fascinated by people like you, who have never played one before, and to hear what your experience with it was like!

It’s honestly been a very intriguing experience to kind of get that feeling like you’re thrown into the deep end, because interacting with a text parser feels very different from, say, a point and click adventure, where you have, sometimes obvious, things or objects to click on. Whereas with a text parser it’s much more involved in a sense. You get this more engaging interaction where it feels like you’re really investigating alongside the main character to unravel the mystery.

Julia: I always feel like with this type of thing I want to ask people about their experience with it. It’s almost like turning the interview around on the other person, like; “Tell me more about your first experience with a text parser”. Because I do find that people say that they get more involved with it, and that they have to participate with it so much more!

Yeah, because you’re thinking in a different way, you’re much less focused on finding ways to progress and things to click on to interact with. It’s more like finding out how to exactly interact with this door; you don’t just click on the door, you have to actually go there and type out ‘Open door’, and that already adds an extra step to the process. At first it felt a bit unnatural, because I wasn’t used to the genre, but it quickly turned into an incredibly fascinating experience.

Julia: I was talking to someone else about this actually, and they said that it almost feels like you’re being taught a programming language, or a whole new language, and how to interact with something in a new way. That’s what the extra difficulty curve is, because people are required to learn what the correct grammar may be, or the set of commands that tend to be the ones that are most common. I understood that this was going to make it a bit difficult. I also already knew that adventure games are kind of a niche anyway, and text parser is actually an even smaller niche within that.

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and your background in game design? How did we get to the point where you decided to make The Crimson Diamond?

Julia: I was really fortunate growing up, because my father was an early adopter when it came to PC’s, and we kind of always had a computer in the house. For the most part we had a Commodore VIC-20. My father would also bring a portable computer home from work. But at that time a portable computer, I think it was a Compaq, was like a 30 pound machine with a tiny little screen that flipped open. He was interested in bringing home games to us, and one of those games was King’s Quest 1! Having played whatever else that he would bring back from the office, it was the first one that really struck me as something different from what I’ve experienced before. Especially when compared to, you know, the arcade stuff and the pinball machines, or Winter Games and Summer Games, and things like that. I did enjoy those, but I really liked the pace of adventure games, and the way it was more about exploring and discovering things. It was when playing King’s Quest 1 that I first discovered text parser, and even at that time I was interested in making games. I remember a Commodore VIC-20 book that was basically just transcriptions of computer games. If you could copy that, word for word, you could create a functioning game, like a text parser adventure or something. I was really young at the time, and I did try to do this, but it was simply beyond me. If you make a single typo in any of it, it’s just not going to work. That was what I first remembered when it comes to making games, which then unfortunately didn’t get very far.

When I got into high school we were learning Turing, which is this programming language that was actually created in Toronto – I think it was based on Pascal, but I’m not quite sure. Turing was great, because it’s basically made to be teaching you basic programming concepts. So I took that course and tried to make a little game. It didn’t work, because it was still pretty challenging to make something with very little guidance on that front. I mean, the bits of programming that I did were all very minor attempts, definitely not to the scale of what I eventually made. Then I went to college to study as an illustrator, specifically to make magazine and newspaper illustrations, and I didn’t really think too much about programming after that. Instead, I became a freelance illustrator for about 10 years, just doing art.

During that time, this engine called Adventure Game Studio had been invented, and people started making games with it! Around the early 2000’s, YouTube became a thing, and people started posting content like let’s plays of adventure games. Sometimes these adventure games would be made with Adventure Game Studio, including Francisco González’s Ben Jordan series, or Yahtzee Croshaw’s Chzo Mythos. It was the first time that I kind of saw that these types of games, that looked and played like the adventure games I remembered, were being made by one single person. That, to me, was really interesting!

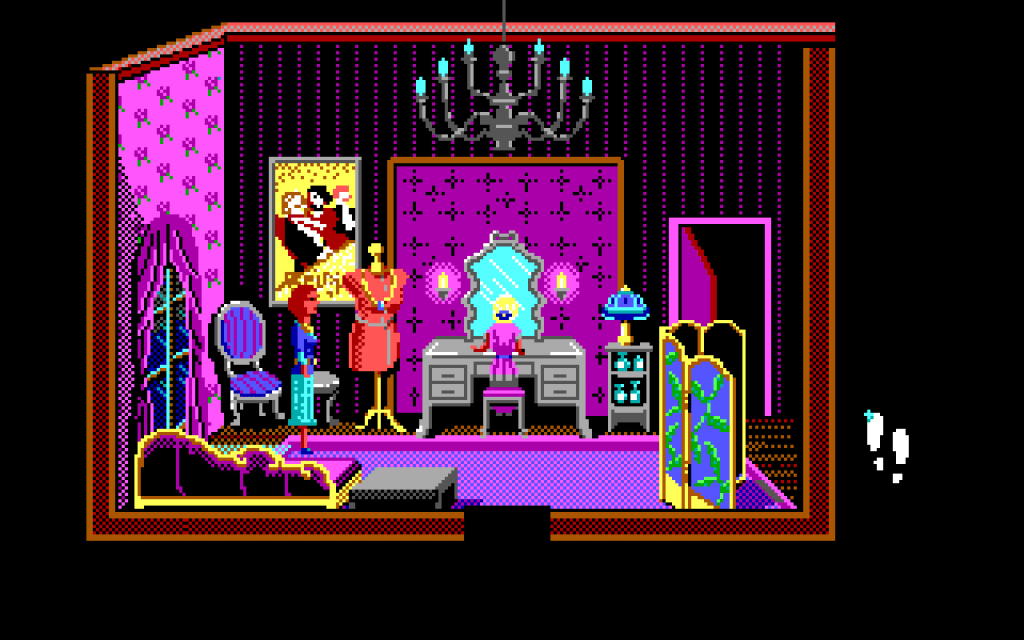

That’s when I started to look into Adventure Game Studio. It was this purpose-built engine to make exactly the type of games that I enjoyed playing the most. YouTube had tutorials for how to, step by step, do these things, and there were also forums available. I felt at that point that it would be the right time for me to actually make a game, because not only was the tool available, but it was also something that was very well documented. It was much easier to use than the stuff I remember growing up with. There were also lots of people that you could talk to and connect with, which was really inspirational for me when I was starting. Although, when I started The Crimson Diamond, at that time I was not thinking about making a game, I was just thinking about trying pixel art! I had been an illustrator for a while, and I went from silk screen printing to just purely digital art. When I saw what I could do with pixel art, I began to recreate the look of adventure games that I enjoyed so much. I looked at old games that I liked and tried to duplicate the effects, based on the limited restriction of the same resolution, which was 320×200. It also had that limited color palette of 16 colors, which I really enjoyed. It gave me a starting point for when I tried to do my own art.

What was that initial spark that made you think that The Crimson Diamond was more than art, and you wanted to make a game out of it?

Julia: I think it was when I slowly started to learn more about using Adventure Game Studio. Piece by piece, when I began to learn things that I wanted to learn naturally, I realized that it could be possible for me to put together something that resembled a game. This became chapter 1 of the game. I mean, it was kind of all made piecemeal, and I didn’t really have a focus for a lot of those early years. I was just thinking; “Oh, let’s make a room here, let’s make a room there. I want a character, so let’s make a character. I want to make her walk, so let’s figure out how to make a walk cycle”. Then I wanted to learn how to stitch together rooms, and how to script that so she could move from room to room. I wanted some doors to open and close, and learn how to create objects in a room, and learn how to animate those objects. I initially started with the text parser interface, because I just enjoyed it so much, and it just so happens that Adventure Game Studios has a text parser built into it already! It doesn’t really get used that much, but it’s there, and it makes my job so much easier. I started with “How do I type ‘Open door’”, and have the parser recognize that to have her walk over and open the door. All this stuff organically lured me into learning more and more. As I learned to do more, I wanted to do more things with it. When I was making the rooms I started thinking “What era is this, what time period? I want to make furniture, what time period would this furniture be from? Where would this place be? What country are we in? What province of Canada are we in?”. The idea of doing this research to decide what the art should be started to form what could be a story in my mind. “Who lives in this house?” It all started with that setting. The setting created the story and from there I thought “Well, I’ve got the start of something here. I’m going to see where this takes me.”

And where it eventually took me was an event called Wordplay in November of 2018, in Toronto, where I live, at the main downtown library. It was a narrative game showcase. I knew it was really tough to get into it, because a lot of people submit to it and they only have 20-25 games showcasing. But I submitted a very rough cut of what I had, and I got accepted! From there I had to be much more focused, because I had to show this to the public for the first time. It gave me a bunch of goals that I needed to make, and I think within two weeks I had managed to put something together, very roughly, to show people at this event. It was a really good experience for me. It was and still is the The Crimson Diamond demo that I showcase during events. From there I already had the rest of the story mapped out in very, very broad strokes. The demo received such a positive reception that I thought, maybe this could be something that I could further develop. And it looks like chapter 1 gave me the confidence to say that I have all the tools that I need, and the know-how to do everything that I want to do with the game. I just needed to expand and do more of the things that I’ve already learned. That was when I thought it would be possible for me to create an entire game.

So how do you structure an adventure game? How do you get from the setting, to the characters, to the story? How do you organize that?

Julia: That’s a really good question, and it’s one that I would like to ask other developers too. The way I started this game was that I wasn’t planning on making a game, which meant that I didn’t start with some grand design document at all. I think that the first time I started generating a design document was around chapter 5, or chapter 6, of a 7 chapter game. The rest of the time I was kind of making it all up as I went along, which is not the best way to organize things! It’s not really a good method of organization, for any aspect really. Not for the story, the puzzles, character arcs, subplots, anything like that. It was very disorganized. Before we started this interview, I actually re-watched my Game Devs of Color Expo Steam stream, and on that stream I dug up some of my old story notes. I found draft 11, which was the most recent draft that I had. It’s a file that I had put together in Adobe Illustrator. It had a bunch of colored paragraphs, and each color was a different character, with everything separated in columns, moving paragraphs from one column to the other. At that time I think there were about 9 acts. So much changed from that draft to what actually ended up in the game. It shows that I did some planning, but that I departed pretty wildly from the plan that I initially had. I didn’t really have an intention or a system to make the entire game.

Because of this, there are some narrative inconsistencies in the game that I need to fix. It’s partly because I didn’t have a good organization system in place, and also because the game has been happening over such a long time. There’s writing in the game that is over 6 years old, and there’s writing in the game that I wrote last week. Quite often I forget what I wrote previously, same with the code. There’s redundant code in the game that I forgot I put in, that I then reprogrammed again. Next time, and I think every game developer will say this, next time I will know better and be much more organized!

What inspired the setting of the game and the character of Nancy Maple?

Julia: I’d like to say that there was a lot of thought put into it, but considering I was not thinking about making a game at the time, I was thinking about making pixel art, it’s not actually the case. The reason I made the sprite at all was because I wanted the doors, the tables and everything to be consistent with the height of a character. Which meant that I needed a character for scale. There were some design considerations, but I mainly needed a character for scale without thinking too much about putting the character in a game.

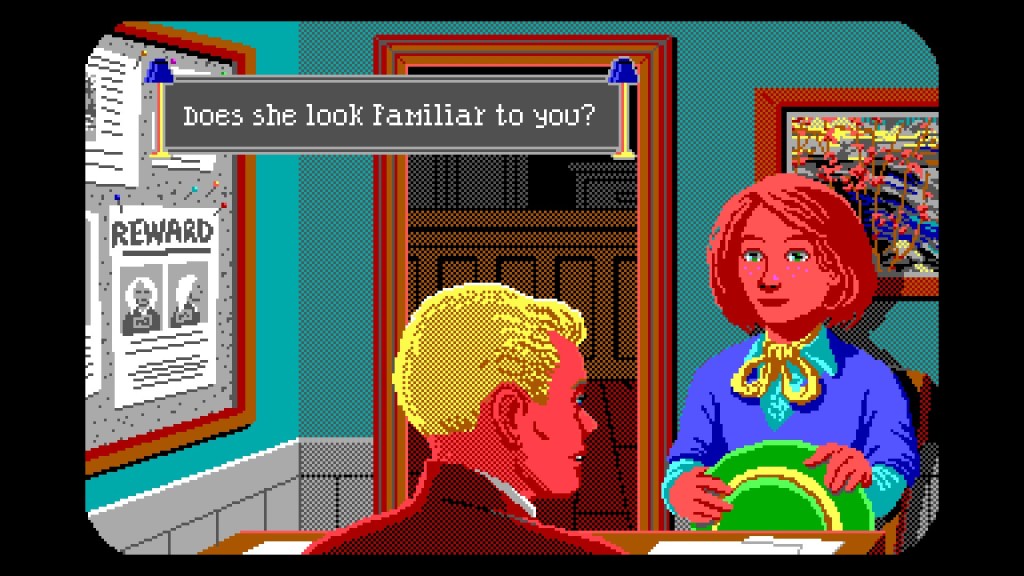

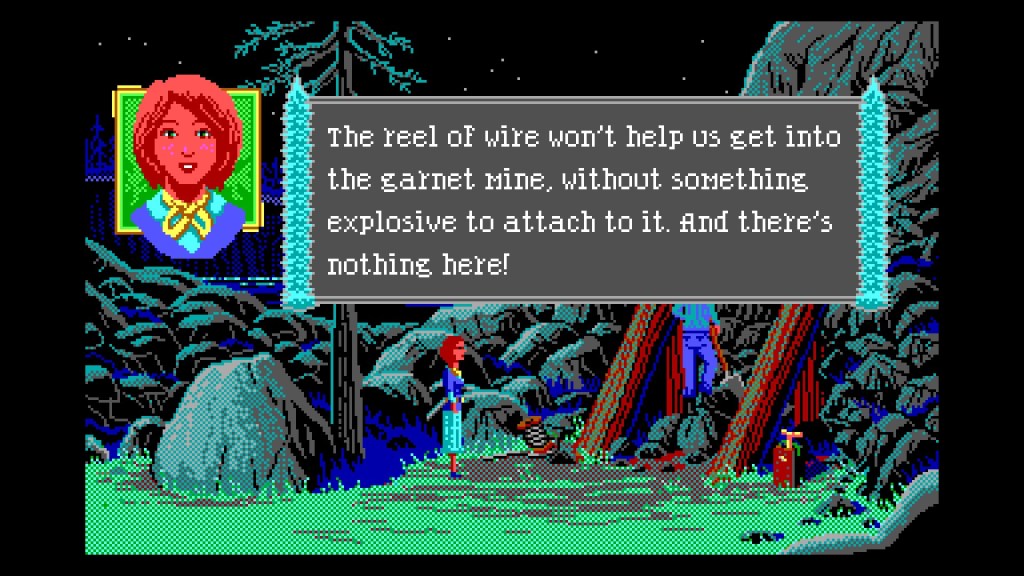

One of my inspirations for the game is “The Colonel’s Bequest”, by Sierra On-Line, which has this redheaded lady protagonist called Laura Bow. Since I wasn’t thinking about making a game, or a story, I thought “Okay, let’s make something like that”. If you put the two characters next to each other you’ll see that they are very different though. But as I started to develop the story I came up with all these reasons why she looks the way she does. For instance, historically, Nancy is born and bred in Toronto, and she grew up in an area called The Ward. At the time The Ward had this huge immigrant population, and a lot of those people were from Ireland, who migrated after the Great Famine of the mid 1800’s. And, okay, Irish people are known for their red hair. I wanted to make Nancy Irish-Canadian, which kind of fits in with her look. And then there was the question of where she would be living at that time, because I knew I wanted her to be from Toronto, since that’s where I’m from. The redhead idea and the game being called The Crimson Diamond also kind of worked, plus she also kind of just looks like Nancy Drew. It all came together in a way that made sense to me. So I kept her that way, and I didn’t really change her that much from her initial design. It started as an afterthought, but coming up with all these story beats gave her a reason to look the way she now does.

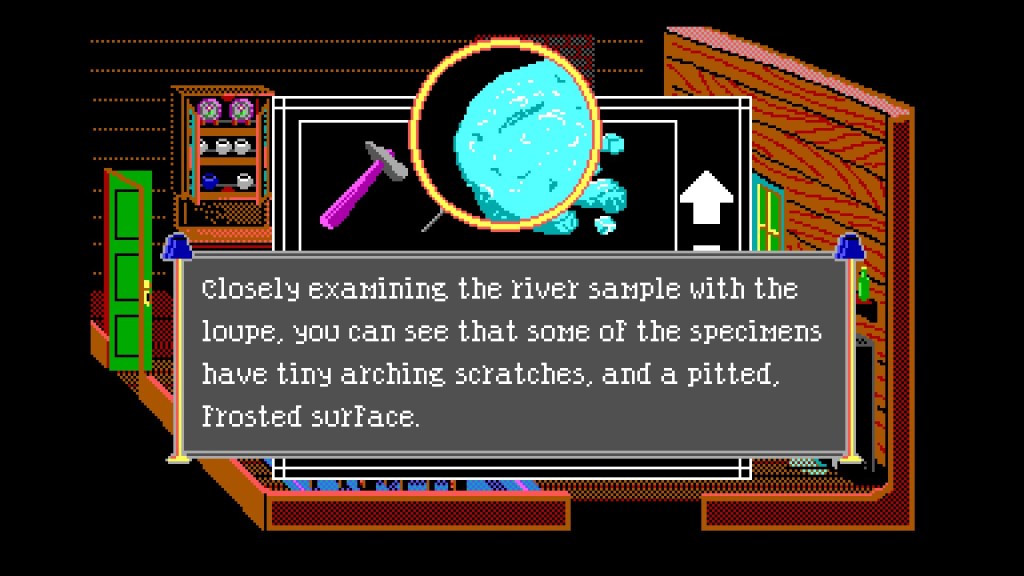

How much research went into making The Crimson Diamond? I noticed during my playthrough that the details with the mineralogy parts were incredibly specific in its approach. Is there a lot of research that you had to do into the field of mineralogy before finalizing the game?

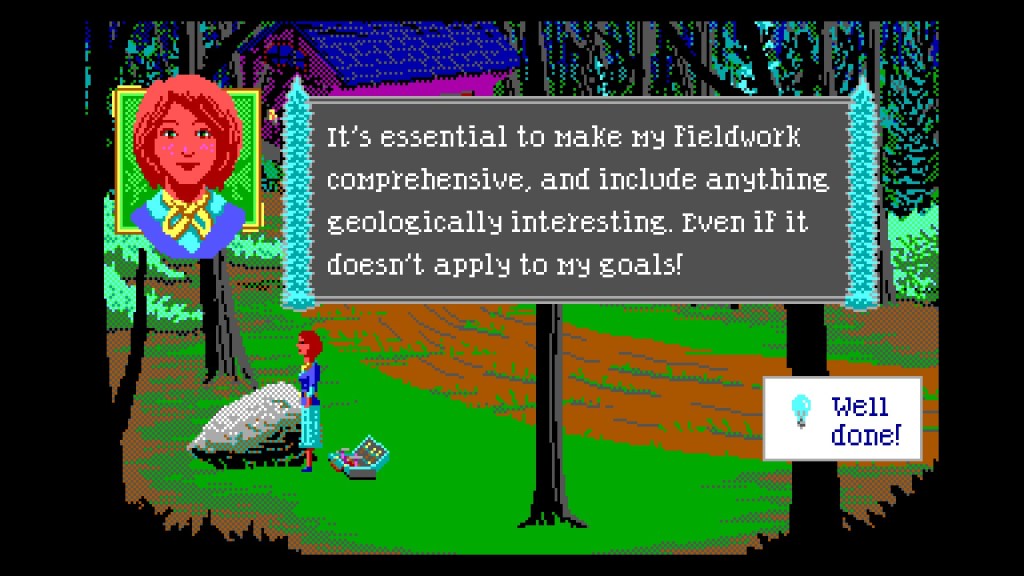

Julia: Oh yeah! I did a lot of research in a lot of different ways. Part of the research was finding out if this would work, geologically speaking. It can, because there actually were diamond mines in Canada, specifically in Northern Ontario and the Yukon area. It all happened much later in Canadian history, we had operating diamond mines in Ontario in, maybe, the early 2000’s. It’s feasible that this could be an actual find, geologically speaking, especially for the region that it’s in. And that’s part of the research that I did. I’ve always been interested in mineralogy and geology, and doing the research for the game really enhanced my interest. I actually got a much bigger rock collection than I did before I started this game. I don’t even think I had a rock collection to speak of before! Now I’ve gone to the Bay of Fundy, and I’ve gotten zeolites from Wasson Bluff, and I went to the Bancroft Gemboree last year in Ontario. It really enhanced my appreciation for it, even though I did have my own interest in it already. I also did a lot of research about early Canada. I looked into the First Nations, because I’ve got a Cree character in the game. And I also hired an indigenous cultural sensitivity consultant, Sonya Ballantyne, to help me with that part as well.

I really enjoyed doing the research, because not only does it make it feel more real to the player, but it also gives more opportunities for background stories. It even gives more opportunities for puzzles based on what you learn. There was this idea of Nancy having to improvise a field kit, but what would be in the field kit? What could you find at the lodge that could act as those tools? All those things came from doing the research and finding interesting and fun ideas that I could use in the game. It was kind of tough for me to stop doing research, and there was a time when I needed to cut myself off, because otherwise I could just go on forever.

Were there puzzles in the game that needed to be changed because it didn’t match your research?

There was a lot more that I wanted to put into the game. And a lot more puzzles that I wanted to put into the game based on the research that didn’t end up fitting properly. It was more of that than having to change things that I already had, because the research came first. Back when I was doing the pixel art and dressing these rooms up with furniture and everything, that was when the research started. That meant that when I started making the puzzles, I had already done the research by that point. If I had done it the other way around, where I’d done the puzzles and then done the research, and found something that contradicted, I probably would’ve had to make a lot of adjustments. Fortunately, at least in that respect, I did things in an order that made sense. I did the research first and from there was able to write the characters, the setting and the puzzles.

Text parser adventures, particularly Sierra On-Line’s games, tended to be a very punishing experience, with frequent game over’s, and the potential to bar you from progressing. Was The Crimson Diamond designed to allow for more leeway, if so, what were some of the things you had to be mindful of when designing puzzles, scenarios and general progression through the game?

Julia: Absolutely! The things you just mentioned were at the top of my mind. I didn’t want there to be softlocks, where you could progress in the game and then get stuck in a place, not knowing that you’re even stuck. Just because you forgot to do something in one of the previous chapters or previous stages of the game. I really didn’t want that to happen. I didn’t want you to be able to die very easily either. Some people do love that about Sierra games, but I was always terrified as a kid by how easily you could die in those games. I remember not enjoying them back then. I also stream on Twitch, and part of my stream is that near the end we play a retro EGA game. It’s been a good way to not only remind myself of some of the stuff that I didn’t particularly care for, but also to play new games. Well, they’re not new games. They’re still 30+-year-old games, but they’re new to me. Either way, I get to discover and take the time to actually play through games that I’ve never played before, or wouldn’t have back then. I get to experience what they did that I loved about those games, but also see what I don’t want to necessarily incorporate into my own game. For instance, something like a limited inventory system, in an adventure game no less. That’s kind of a brutal limitation, that probably was a case of, maybe, a technical limitation. It’s something we don’t have to worry about these days, and it’s not something that I wanted to build into my game.

Is that where the joke about Nancy having really deep pockets comes from?

Julia: Yeah, exactly! Sometimes I make an excuse like you can’t carry around a whole shovel. There are certain huge objects that you can’t put in your pockets. The overall feeling of the game that I wanted was this idea of a cozy mystery, and that you’re kind of being taken care of in a way. It’s more of a positive environment that is, I don’t know, not hostile in a way that some games can make it feel. Like when they’re telling you that you can’t pick that up because you can’t carry any more things, or because you missed a thing. I wanted to give the player as stress-free of an experience as possible!

Part of that is not only looking at the old games, and learning about the things I liked and didn’t like, but also playing newer adventure games. There’s the notebook in the game that tracks your progress, and I got that idea from Thimbleweed Park. Sometimes you have to step away from a game, and then you come back and don’t remember where you left off. That can be a very real barrier to picking up the game again. I really loved that Thimbleweed Park had something like that available and I wanted to have that for my game too.

Is there a similar effect happening in reverse, where the things you learned from making The Crimson Diamond changed your perspective on other adventure games, and the way you approach them?

Julia: I think what it has done is that it made me respect so much more of what they did back then. Part of that is that I have the advantage of making my game now. I have all these easy to use tools, people to help me, and tutorials and everything. Back then, a lot of the time, they were developing the tools at the same time as they were developing the games. It’s this level of technical wizardry and artistry that I can’t approach. I’m not a tool maker. The idea that they were doing both of those things at the same time, I mean, you don’t even just find that in games, you find it in movies as well. Inventing these processes for special effects at the same time that you’re making the shots and everything. It’s this level of inventiveness that I appreciate so much! They were inventing a completely new genre. Which means that, sure, there were things that were better not to do in certain ways, but we have the benefit of decades of experience in game design. We can make those choices and change things that didn’t work as well, or see things that did work really well. I have so much respect for those people that were just blazing that trail, because there was nothing to compare what they were doing. They were inventing something completely new.

It’s definitely something that you can see in the arcade scene, in particular moving from the late 80’s the early 90’s, where you start to see that iterative process of designing better games based on the, I’m hesitant to call it that exactly, mistakes of the past. For me, a great example would be going from Street Fighter 1 to Street Fighter 2.

Julia: The type of thing I think I particularly love is when you look at one particular console and you see the early games that are built for that console, and then later games that were built for that console. It’s the same console, but people have a greater understanding of what is possible and what those technical limitations are, and how to work around them. The games look so much more advanced, but it has nothing to do with the hardware, it has to do with people’s knowledge. I really find that an amazing process!

What were some of the major challenges that you had to face when making an EGA inspired text parser for a more modern audience?

Julia: There are a few. I think we discussed it a bit earlier, with there being a difficulty curve of needing the player to have a higher level of engagement than they would otherwise. They’re the ones who have to generate these commands to type into their keyboard. Part of that is easily solvable, though I certainly didn’t do it perfectly, where the writing in the game has to be very specific. You have to try to be concise because you don’t want the player to have to wade through sentences and sentences to find the keywords that they’re going to need, the nouns and verbs that they’re going to need. That takes some consideration, because they can only rely on your text descriptions to learn what they can do. That part is something that has to be kept in mind. Another part of it is that people use different words for the same object, based on things like where they live, or what generation they’re from. Like trashcan, bin, waste paper basket. There’s a number of things to call that object. Watching people play the game at events, but also watching streamers play the game from all over the world, has been very educational. That’s part of the challenge of a text parser versus a point and click game, because people will have different words for things. Fortunately it’s very easy to add synonyms in Adventure Game Studio, and I’m happy to add synonyms for people that think that I should. I recently got an example from a British player; waistcoat isn’t a vest, because a vest means something else in the UK. So I added waistcoat as a synonym for the people that are more familiar with that term.

Those types of things can be tricky, and also, this idea that people have an issue with coming up with exactly the right thought or the right sentence. They may have the right thought, but constructing that sentence can be a bit tough. The way I address that is that I will try to add those ways of saying those things when I can to the game on updates. But I also have the in-game hint book that you can open in a web browser and hopefully that might get you the right wording that you need to get past something that is a bit frustrating.

How do you choose the right words and prompts, and how do you guide the player in that direction?

Julia: There is an art to that, which I have not mastered yet. It’s something that I do think a lot about when I’m making the game. It certainly has been the case where, when I watch people play, that people tend to get stuck in the same places. And that’s where testing is so valuable to me as well. I had a wonderful group of testers who really put the game through its paces, and helped me find some of those parts. I mean, it’s really hard, because maybe you have like two dozen testers or something, and when you launch a game all of a sudden thousands of people are playing it. They’re going to find things. Another aspect of this is that the game has been speedrun by the adventure games speedrunning community. And if anyone is going to find bugs or issues, or make suggestions on how to maybe make things smoother, it’s the speedrunners. Because they put the game through its paces like no one else would. It’s a matter of knowing that, when I launched the game, it wouldn’t be perfect, and that I’d still have to continuously fix it and update it. I’m really motivated to do so, because I want the game to be a really good representation, and possibly a gateway to other text parser games that people might enjoy. I want people to have a positive experience with it.

What are some of the things you’ve learned from developing The Crimson Diamond?

Julia: One of the biggest things is how helpful and patient people can be. This game has been in development for years, and years, and years. I’ve had people tell me in reviews, or by messaging me, or by email, that they’ve seen the game like five years ago, and that they’re really glad to see that it’s out now, and are having a really good time with it. I don’t think there has been a single time, and I don’t want to jinx it, when anyone has said “Where is this game?”, or “Why isn’t this game out yet?”. For the most part people have been incredibly patient and super encouraging. I’m so happy to know it worked out that way. That’s the first thing.

The second thing is that sometimes I needed a lot of help with the game. There were certain times where I couldn’t figure out certain bits of programming. Even up to the last couple of weeks, trying to get the achievements working on different platforms. And just how willing people are to spend time to help you with those things has been really life affirming, I guess, in a ‘faith in humanity’ type of situation. You sometimes don’t know how wonderfully helpful people can be unless you need that help. In so many ways this game could not have been finished without the help of those wonderful people. And I try to put them in the credits as much as possible. Even people that I’ve never spoken to that made a plugin for Adventure Game Studio that really helped me, I put them in the credits as well because it’s all part of this community of really passionate, wonderful and knowledgeable people helping each other. And think that’s one of the most inspirational things I’ve experienced when making the game!

How do you write a puzzle or mystery that requires that specific knowledge of things like mineralogy, the streak plate puzzle in particular?

Julia: That was the benefit of the research. It’s not 100% accurate, because there’s actually different kinds of streak plates, and that is something that I did not end up doing in the game. Usually with a field kit you’d have a white streak plate, a black streak plate, and a glass streak plate. It’s one of those things that I just streamlined into that one type of thing, just for simplicity’s sake. Also, when things get kind of elaborate, I was doing flowcharts and everything. One of the reasons I needed flowcharts for a few of the puzzles was because some of them could be completed in a bunch of different ways. For instance, when you get Jack’s fingerprint, there are a number of ways to achieve that. I didn’t do that for every puzzle. A few of the puzzles have that feeling of replayability, well not really replayability, but different ways of doing them. I’ve had people say that when they watch other people play it, they’ll see them solve things in ways that they didn’t know about. Or they’ll see things that they didn’t experience in their own playthroughs. That is one of the ways that I was really thinking about how to encourage people to play the game even if they’ve seen other people play it. Or to encourage people to replay the game if they played it once. I really wanted to encourage that replay aspect of it with certain design decisions. Even though the game, as an adventure game, is, by design, fairly linear. One of the ways to do this is by having the puzzles be solvable in different ways. This makes them much more complicated, which means that I had to occasionally use so-called “puzzle dependency charts”.

I ended up missing a few items to progress the most straightforward way, but managed to dig myself out of that hole with a small hand shovel. Is that also something that you use to your advantage when putting these failsafes in place to prevent players from being locked out of progressing? Is the fact that you designed the puzzles to be solved in multiple ways also part of that?

Julia: In some instances, yes, it’s almost like an insurance, but against my own mistakes. There are some ways where, for instance, you’re looking for shoe sizes. Sometimes, for whatever reason, you can’t access a certain person, or you can’t ask them a certain thing. You can ask the ranger about people’s shoe sizes, because he’s very observant. He’s this police officer basically, so he’s trained to do that. In which case, for most of the people, you can ask him about their shoe sizes and he’ll give them to you. That’s another way to solve that puzzle, but in a way that is, kind of, just in case something isn’t working in the game. I sometimes made these redundancies as well, to make sure that, even when it’s not working, you can get it some other way. So yeah, for sure! Unfortunately, because, again, I mentioned that lack of organization, I felt like I was trying to hold it in my head all at once. It’s very difficult to do, and I don’t think I was very successful in that, but I would say that I tried as much as possible. I don’t think there are any softlocks by design in the game, and hopefully no one is going to find anything. But the idea of trying to think of all the possibilities, when characters are moving around from room to room, sometimes they’re inaccessible, so trying to make it so that all the objectives are possible, even when all that is happening, is very challenging.

When you’re designing these failsafes, what is the first thing you’re looking for when there are a lot of moving parts happening at the same time? What is the train of thought for making a back-up plan for that?

Julia: There’s a lot of flags and checks that can be activated, and things like that. Unfortunately you can do a lot of stuff out of order in the game, which tends to really complicate things. I was watching someone stream the game last night and they were in chapter 2. In chapter 2 you’re gathering your improvised kit to get your samples, and by the time this person was in that chapter, not even finishing it, they got the shoe sizes already, and they didn’t know why they had done it. I’m kind of curious, I did not test it that way, and I don’t know what’s going to happen. I think it should be okay. But the idea that you could do all these things out of order was because I couldn’t think of a reason why you couldn’t do them out of order. There was no rational explanation why you couldn’t look into Corvus’ shoes at any time and get his shoe size, right?

People have often picked up the ice pick in chapter 1, just by being thorough. Of course, it also adds this extra layer of complexity to it, because I didn’t design it so well that you couldn’t do those things. Part of the reason that I didn’t was because I wanted people to feel free to do things. I don’t want to give people that response of “You can’t do that right now” if I can help it. I couldn’t rationalize a reason why they couldn’t so I just let them. Again, that does make things more complicated later down the line. I really hope that this person is able to finish the game and that the flag gets tripped when you need all those shoe sizes at the appropriate time. I’m hoping that works out for them. And it should, but I did let things get more complicated by letting people do things out of order.

That does give the game some natural sense of progression. Just being able to go somewhere and actually be able to interact with the environment instead of being limited by, like you said, flags that say “You can’t use that right now”.

Julia: Yeah, because that’s really confusing for players too. I know that in some games it will say that. They’ll be able to do it later, and then they’ve already just completely discounted that thing as an interactable that’s useful, because they were told that it wasn’t useful at a certain time in the game. Or there’s no message at all. I certainly didn’t want to do that, but you kind of have to make these kinds of choices in game design, about what you think is best for what you’re making. What is going to add to the game versus how much is it going to take away, are decisions that are kind of tough to make. And I try not to sit on the fence too long about them. I’ll just try to decide one way, and when it doesn’t feel right I’ll just switch it back. Sometimes you just have to commit to one decision and see if it’s going to work or not for you, instead of just being indecisive about it.

Was the omission of the word “Use” intentional?

Julia: Yes. Very much so, because it’s too easy. It’s too versatile, it would be the tool that you’d use. It’s like having a gun in your game, you’d just want to shoot everything, right? That’s going to be the answer to every problem. When you take “Use” away it does challenge people. And I’ve heard different arguments, and I think they’re often completely valid. “Use” is very useful, of course, but also some people do appreciate the fact that I don’t let the player use “Use”. There’s just so many verbs available that say much more about what you’re trying to do. “Use” is just so vague. And it’s great, because it is, but I didn’t want to have players to want to use it as the one solution to every problem.

So it’s more to encourage players to actually think about how they want to do something? More a case of not using “Use cookie and wax”, but more along the lines of “Put wax in cookie”?

Julia: Yeah, like “Use wax on cookie”, or “Use cookie on this”. It’s not really telling you about the action you’re actually performing, you know? Which makes it such a powerful word, but at the same time for the text parser I wanted to encourage people to actually think about what they were trying to do.

That makes sense. Especially given that it already does a lot of things to streamline the text parser elements to make it more accessible. To create an extra layer of immersion, as well as introduce players to the way that you need to approach these types of games.

Julia: At the time when graphical text parser games were around, and when games moved on to the more point and click interface, there was this idea that we’ve advanced beyond the text parser. Now we have an improvement beyond the text parser. And in certain ways it is, because the point and click interface is easier to port to other platforms and consoles. The usability is definitely a lot easier, but I myself would never say that the point and click interface is an improvement over the text parser. Just speaking of the overall enjoyment you can get out of a text parser, I think, offers something different than point and click does. I think that they’re both very valid ways of interacting with a game, but in the same way that I don’t think VGA was an improvement over EGA. It’s just a different style of making the artwork, but at the time it was considered an improvement, because now we have more colors so therefore it must be better. I don’t necessarily feel that way.

Is that also part of the reason why “Use” was omitted? To avoid the game from feeling too much like a point and click?

Julia: I’m not sure if that would make the game feel more like a point and click, but at the same time I knew going into making this game that I was not trying to make it the easiest game to play. In some ways I was trying to make what I decided to do as easy as possible, but at the same time I knew there was going to be some friction. It is a harder interface to use and I will totally admit that, but at the same time there’s some aspects that I was unwilling to lose, and I was unwilling to sand off that particular edge. I do think there’s something there that is more engaging in deciding not to use the word “Use”.

The last point and click game I played was the horror game; Stasis: Bone Totem, and it used a lot more visual elements to tell its story. While I was writing the review for The Crimson Diamond I was thinking a lot about how the two different genres approach immersion. And I realized just how much I felt like I was investigating alongside Nancy. I got really excited about opening drawers and stuff to see what’s in there. It’s a really unique sensation that you get from it that I don’t think I’ve ever found in another genre.

Julia: I’m really glad to hear you say that, because I’ve always said that the text parser is my favorite way of interacting with a game. And I think there’s merit to it, and would like to see more of it. Especially nowadays where it’s so much easier to make a text parser game. It’s much easier than it used to be. I would love to see more of this level of interaction or this type of genre. I love hearing from people that have never played a parser game. I’ve seen some younger streamers play it, and it’s something completely different from what they’ve experienced before. I think it’s fantastic to know that people can feel that, and it’s not just some nostalgic feeling, because they don’t have that nostalgia. It doesn’t exist for them. There is something beyond that, that has an entertainment value to it. And it’s compelling in a way that I felt when I was playing these games for the first time.

I think the closest I’ve gotten to playing a text parser game was Glass Rose for the Playstation 2. In that game you have to highlight bits of text to navigate your way through the story, and inquire further into the dialogue. It’s a really cool concept that sort of feels like an evolution of this. You create this visual element, but still create that same, or similar, level of interaction or player input. It’s a really interesting game that I think you might like.

Julia: Oh, this looks really cool. I love the idea of using a language in a different type of way or using a different type of interface to try something. Other game developers I’ve spoken to are talking about trying to simplify. And I understand why you’d want to simplify, because what it does is that it gives us this potentially larger audience that we can reach. I think that’s a good way to go at it, especially with narrative games. I think narrative games as a whole are more approachable than something like Elden Ring, which is a much more challenging, dexterity based game. In a story based game, or a visual novel, there’s a lot more opportunity to reach people who have never played a game before, and have them experience and interact with a story like that. It can be a really nice gateway to games. All humans love a good story, and when you can interact with that, it adds that layer of being compelling as a medium. Only games can do that. I value having that ability, but at the same time, when I make a text parser, I know that I’m limiting myself to people who either have those nostalgic feelings, or people like you, who are going to take an hour to feel lost and gradually get accustomed to what the game is doing. I don’t know how many people I can possibly expect to take that hour, because there’s so much demand on people’s time nowadays and the competition is so much greater than it used to be.

That is true, but I do feel that The Crimson Diamond released at the perfect time of year to slow down a little bit and curl up with a good book, or adventure game in this case. This game was perfect for that. I played this right after a massive heatwave. The weather suddenly turned a lot colder and it started raining, so I decided to make a cup of tea and really sit down and enjoy the game. For me, that was the perfect setting for it. I think this is the perfect time of the year to introduce people to these wonderful text parser games.

Julia: Good! I like how you mentioned that it’s such a cozy game, like curling up with a good book. My design philosophy was that I wanted to make it feel more like a book than a movie. What was important to me was that I wanted the player to be able to set the pace. Part of that was that text boxes aren’t going to clear until you clear them, they’re not on timers. The game itself is not going to progress until you’ve explicitly done what the notebook says. You’re not going to accidentally progress the game. I tend to get stressed out when I feel rushed, you know. Like when, in a Mario game, the music starts to speed up when you have less than 100 seconds left. That is not fun for me. I like to take my time, I like to set the pace, and I like to dictate when the game moves on. And that’s stuff I thought about a lot when I was making this. It works, not only for my personal feelings and how I like to enjoy an adventure game, but also in the genre of it being a cozy mystery. Where it feels like there are dramatic things happening, but it’s, for the most part, something that’s going to be a cozy, relaxing afternoon type of feeling. The kind where you’re going to curl up, have a cup of tea, and will have a nice little experience with this game. It’s not going to stress you out, it’s not going to make you anxious. It’s going to be this, hopefully, warm and enjoyable experience!

Do you have any other interests, or things that you love, that didn’t make it into The Crimson Diamond, but that you want to maybe use in future projects? Possibly a sequel?

Julia: YES, absolutely! I do have sequel plans. I have lots of sequel notes. One of the things I would love, I don’t know how much I’ll actually incorporate into my next game, but I love seeing pixel art renderings of food. I didn’t have much of that in my game, well I have a little bit, but I would love to do more of that. That’s the first thing that came to my head that I would love to have in my game. Even things like mechanics. Certain mechanics that I really enjoyed in other games that I didn’t get to put into this one. I could see them maybe fit into the next one, and I’m really excited about exploring those parts too.

Any that you can share?

Julia: That I would have to stay super vague with, but I will say that in the era that this game is, which is 1914 -I will say that I love art nouveau, I love art deco- I would love to explore a more stylistic art deco look for the next one. I’m thinking about The Dagger of Amon Ra and how beautiful I thought that game was, and I still think about how art deco inspired it is. I would love to do something that’s more art deco in my next one.

Is that possibly a new adventure for Nancy Maple, or are we going to see a whole new cast of characters?

Julia: It’s going to be another Nancy Maple Mystery! Another thing about this next one is; Some people had said that they found that the characters in The Crimson Diamond are kind of basic and stock characters. People say that you kind of know who the bad guys are very early on in the game. Although you still need to prove it, and you still need to come up with the evidence. Also, the genre of cozy mystery tends to have very stock characters in a way. But I will say that in the next one I would probably do a bit more of a subtle, nuanced story, maybe with a bit more subtle characters. One of the reasons I didn’t do that with this one is that the genre encourages more stock characters, but also because this is my first game. This was my first time really writing anything fictional, and I wanted players to understand what the characters were, and what was going on. I kind of purposefully made them pretty simple. Although I will say that people really have their reasons for things, and I do tend to sympathize with Nessa in certain respects. Maybe in the next one I would enjoy the challenge of trying to do something that is a bit more subtle.

Personally I never really got the idea that the whodunit was the focal point of the story, more like a catalyst to move the story and further investigate the mystery. More like; how do I get to the point where I can prove that it’s these people behind the murder. That’s more what it felt like to me.

Julia: I think that when making something like this, of course there’s going to be a lot of different opinions about it. There are a lot of people that do feel the same way as you do.

Now that The Crimson Diamond is released, are there any games you can now sit down with and play?

Julia: Absolutely! I backed Skald: Against the Black Priory, that amazing pixel art RPG. I backed it ages ago, and it’s come out quite a while ago now. I’m so looking forward to getting into that! I actually started loading up Judero over the weekend, which is this incredible stop-motion, Scottish folklore game. I started playing that as well. There’s so many things I want to get into. From the top of my mind, something I’m very excited about; I have Tokimeki Memorial on my Anbernic. I loaded up a ROM on it and I want to play that. I’m trying to teach myself more Japanese and I think that’ll be a fun opportunity to try that.

Oooh, that’s a rabbit hole!

Julia: Oh, I know! I’ve seen the Tim Rogers video about that and wow. What I love about that game, and games like that, is that it’s deep, but it’s deep because it’s content deep. It’s not deep because there’s a lot of 3D art and it’s super realistic. The art is pixel art. It’s a AAA-game that looks like a visual novel, but has incredible systems and incredible depth. I’m very much looking forward to getting into that as well. I have a Playdate. There’s a ton of games on Playdate that I’d like to play. I know Lucas Pope has a game on Playdate that came out maybe months ago now, and I would love to see what that one’s up to. There’s so much that I want to try that I had to put on hold. At this point, now that the game is launched, I’m still trying to figure out my routine. It’s been a bit of an adjustment period.

Because so much time has gone into developing The Crimson Diamond?

Julia: Yeah, and especially the last month or so leading up to it was really intense in terms of what I needed to get done. Things that needed to be done correctly so that the game could launch properly, and all the promotion that I had to do for it. And I’m still kind of in that mode as well. That’s a bit hard to readjust from. I spent a lot of time, especially in those times, to finish the game. I still have tons of bugs to fix, so I’m not too worried about having anything to do. But yeah, it’s kind of tough, because I really like having a nice routine going. It’s a bit of a thing where post launch you just kind of feel a bit aimless. Well, just a little bit.

I can imagine finishing a big project like that and having that moment of “What’s next?”

Julia: Yeah, “Who am I now?” even. The game has been going for so long, and my life when it started and my life now is very different. Just this idea that now this chapter of my life is over. “What comes next?”. I was doing contract work on games like Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator, Witch Strandings and Recommendation Dog!! during most of the development of The Crimson Diamond. Only in the last two years before launch did I really focus on finishing it. It was self-funded and self-published, and now I have to evaluate what I’m going to do now. Am I able to fund my next one? I mean, it’s too early to tell at this point whether I can or not. Am I going to do contract work? Basically I’ll repeat the process of The Crimson Diamond, where I do contract work for a lot of the development time and just focus the last two years on finishing the game. Will I do some crowdfunding? I really have no idea what’s going to happen next. That’s something that I need to work on getting better at feeling, because I really like to know where I’m at with things, and when I’m not, I feel unanchored. That uncertainty I’m not super crazy about, but we’re just going to have to see where it goes.

I guess it’s a bit of a step by step process. Maybe play a game first and kind of wind down?

Julia: Yeah, yeah, that has been the suggestion to me a lot of the time. Have a break! Have a break! It’s even hard to wind down sometimes. I am actively also trying to do that!

I mean, it’s difficult to go from fifth gear to a more relaxed state of mind.

Julia: Yeah, I only really feel like I’ve gone into that state this week. Last week the game launched on GOG, and getting something up on a new storefront, there’s a lot of stuff that has to happen in the backend. I had to create a bunch of assets, and I had to make sure to learn their backend – which is different from Steam’s backend. Just getting it up and launched on GOG feels like the last big thing that I needed to do before I could slide into a more of a maintenance mode. It feels like everything is now in place, for the most part. And now I can feel like my job is done. The game is up on Steam, Itch.io, GOG, Fireflower Games, and now I know their systems. So when I need to make an update, I’m familiar enough now that those things can happen. Learning the backends of storefronts was a whole other thing too. There’s a lot of learning involved, and that can be super challenging. Especially when you’re at the end of something, you kind of feel a little bit burned out, and having to learn something new at that point just feels like this insurmountable goal. But just like any other part of the process, you just take it step by step, and eventually it just gets done. And now that I’m entering this week with everything pretty much done, I’m starting to feel better about it being somewhat finished!

A massive thank you to Julia Minamata for taking the time to sit down with me and talk about the journey of The Crimson Diamond’s development and release. If you want to read more about The Crimson Diamond, TanookiChickenAttack has a review available for you to read, but I do recommend giving this absolutely marvelous look into a modern day snippet of the past a go yourself first!

You can find The Crimson Diamond over on the following platforms;

Website https://www.thecrimsondiamond.com/

STEAM https://store.steampowered.com/app/1098770/The_Crimson_Diamond/

GOG https://www.gog.com/en/game/the_crimson_diamond

FireFlower Games https://fireflowergames.com/products/the-crimson-diamond

Itch.io https://juliaminamata.itch.io/the-crimson-diamond-full-game

Check out more from Julia Minamata, and be sure to send some support;

Website https://www.juliaminamata.com/

Patreon https://www.patreon.com/juliaminamata

Twitch https://www.twitch.tv/a_maplemystery

Youtube https://www.youtube.com/c/JuliaMinamata

X https://x.com/JuliaMinamata

Mastodon https://mastodon.gamedev.place/@JuliaMinamata

Bluesky https://bsky.app/profile/juliaminamata.bsky.social