2024 | Bokeh Studio | Playstation 5

This review contains spoilers for the game’s story

Like the holes in The Enigma of Amigara Fault, this game was made for me; this is my hole! I’ve been a fan of Keiichiro Toyama’s work for a very long time, even with thoroughly enjoying the rather obtuse and insane experience that is Forbidden Siren. So when Slitterhead got announced from a brand-new studio featuring Toyama AND Akira Yamaoka, I was beyond ecstatic! A horror game by two industry legends set against a backdrop of a fictional rendition of Kowloon? Sign me right up! I had to wait a little longer to get to this game, because there’s no physical release in Europe, but the US did get an incredible Day One edition. I haven’t been this deeply excited to cover a game in a while, and upon booting it and playing for a few hours in my first session with it, I can say; This was made for me, this is my hole!

From Silent Hill to Bokeh

Originally revealed in 2021 at the Game Awards, Slitterhead was the debut project for the in 2020 founded Bokeh Game Studio, by none other than industry legend, Keiichiro Toyama; the father of Silent Hill, Forbidden Siren and Gravity Rush, and joined by Akira Yamaoka, a composer of equally legendary stature. The trailer showcased an intense sequence of events with a man getting assaulted by a monstrously skeletal creature that hid inside of a woman, the streets being covered in gore by insectoid monsters with human faces, accompanied by a rushing guitar riff. This bit of the trailer got me excited, but what got me squealing for joy was the fact that the end of the trailer seemed to present the setting as none other than Kowloon, a horror game set in one of the most fascinating human constructions ever built.

It felt like a blast from the past to see these gaming industry veterans tackle their home turf genre with such a fascinating setting. Keiichiro Toyama and Akira Yamaoka both made massive ripples across the industry with the 1999 release of Silent Hill for the original Playstation. While Yamaoka continued to oversee the development and provide music for the series, Toyama moved on to work on a different horror series, which would build the foundation for Slitterhead years later; Siren. Which is a rather cryptic experience about a village being overtaken by an alien entity. The game was designed as a massive puzzle with real life message boards serving as a collective puzzle solving hivemind. The game received a sequel with Forbidden Siren 2, which only received a PAL release in the west, which streamlined the game to be more of a single player experience, rather than a group effort.

The original Siren would receive a “reimagining” of sorts in the form of Siren: Blood Curse for the Playstation 3, which removed the cryptic progression in the form of a more chronological, stage-based progression with optional objectives listed out for more information. This solved the problem that the original had, where most of the progression was hidden behind specific tasks that weren’t disclosed to the player, thusly making it more of a group effort to share bits of information with one another to actually beat the game. This title took a strange approach and recast most of the original characters as American documentary crew members looking to make a documentary on the events that happened in the original Siren, but it still retells the same story as the original. It’s kind of like watching the 2004 American remake of Ju-on: The Grudge, but it’s the original movie at the same time.

From the strangeness of Blood Curse, Toyama’s portfolio took a tonal whiplash with one of my favorite VITA titles; Gravity Rush! An excellent action adventure game in which you control a witch that manipulates gravity. With this game and its sequel, Toyama showcased his competence in creating complex and interesting stories, but also showed a habit of obfuscating the obvious at times. After leaving Japan Studio, he founded the independent Bokeh Game Studio and started working on a brand-new horror game alongside his old partner Akira Yamaoka. The game featured creature design by Siren’s character and monster designer, Miki Takahashi, and character design by none other than Breath of Fire and Devil May Cry veteran, Tatsuya Yoshikawa. And the music was, naturally, made by Akira Yamaoka. The game boasts an impressive level of creativity in concept, but the execution shows an ambition that felt like it drastically exceeded the budget. Which, in turn, does leave the game in a weird vaccuum.

Narrative singularity

To say that the narrative of Slitterhead is a bit of a convoluted mess would be a pretty massive understatement. It weaves a complex web of convoluted plot points together into a framework of bootstrap paradoxes inside of bootstrap paradoxes, with time traveling ghosts that hunt parasitic monsters underneath the hard rock neon lights of Kowlong. The closest experience I can think of is the Colonel’s “I need scissors, 61!” line from Metal Gear Solid 2, if it was an entire video game. At the surface it may look non-sensical, but bear with me here.

The game follows a disembodied entity named Night Owl, a Hyoki spirit, that has the ability to possess humans and certain animals. He wakes up in Kowlong in the early 1990’s without any memories of how he got there. As the disorientation fades, the spirit realizes he can possess the mind of others and proceeds to hijack the brain of a nearby dog to further explore the labyrinth of alleyways that he now inhabits. For a while all you seem to need to do is track the scent, that is until you’re chased away by an angry man. Let’s try to see if we can hitch a ride in the body a bit further down the alley. A bit wobbly, more difficult to maintain balance, but with a bit of stumbling and swaying, the spirit manages to further navigate the maze. After hopping through a few minds we get our first introduction to the reason of the Hyoki’s arrival. A woman approaches the possessed man making offers of good times. The woman starts to stretch, her head and neck distorting into a grotesque form, and she relentlessly pursues the Hyoki. The first introduction to the Slitterheads is a frighteningly effective moment that is equal parts weird and terrifying. In order to escape you have to frantically skip from mind to mind like a rock skipping over the water surface, with the monstrous form ripping through the crowd in order to catch you.

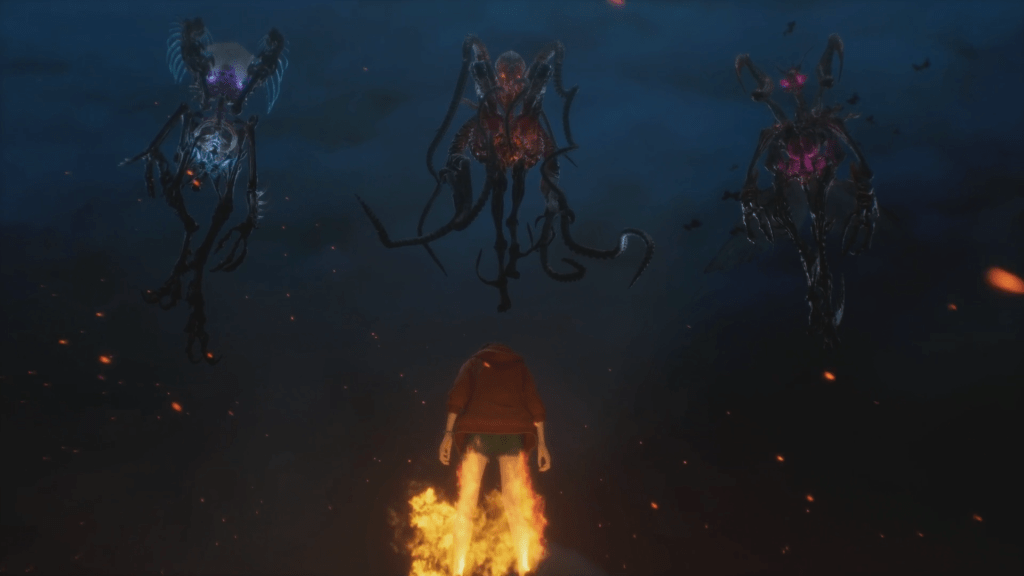

After escaping your pursuer, your vision starts to fracture, and suddenly we find ourselves looking through the eyes of the monster staring down its next victim. This prompts the spirit to find out where the creature is and defeat it, but during the fight something happens. Upon possessing the girl the monster was trying to devour, a strange sensation engulfs the spirit. The girl seemed to have an increased affinity for merging with the Hyoki and exudes a special power. This is the introduction of our second main character and first Rarity; Julee. The possession saves Julee from her fatal wounds and together they manage to destroy the monstrous Slitterhead. During the fight a mysterious figure shows up that is later revealed as the hunter, Alex. From here we get introduced to a slick looking overworld and even slicker looking dialogue sequences. At this point the game also introduces the three main antagonists in the form of three unique Slitterheads, which in turn translate to three story branches that intertwine with the overarching plot; A mysterious cult that houses both Slitterheads and humans alongside on another, seemingly living in harmony, a brothel whose proprietress feeds her customers to the monsters, and a time traveling Slitterhead whose existence pushes Alex over the edge.

Throughout the game you get to freely interact with these three story branches up until a certain point. Of all the Rarities, Alex is the most overwhelming of the personalities, and manages to engulf the Hyoki with his drive for vengeance. This robs the spirit of any identity to the point that he becomes nothing more than a tool in the hands of a rampaging murderer. Along the way you’re given hints that there’s more to the Slitterhead than a simple monster parasite invasion. In classic Siren fashion, the game quickly spirals into a maddeningly intriguing plot of the end of human existence, time travel and anger issues. With each loop the amount of monsters you face become more overwhelming and organized. At first it might seem innocent, but you’ll quickly face masses of phallic shaped enemies.

Time is a flat circle filled with bootstraps

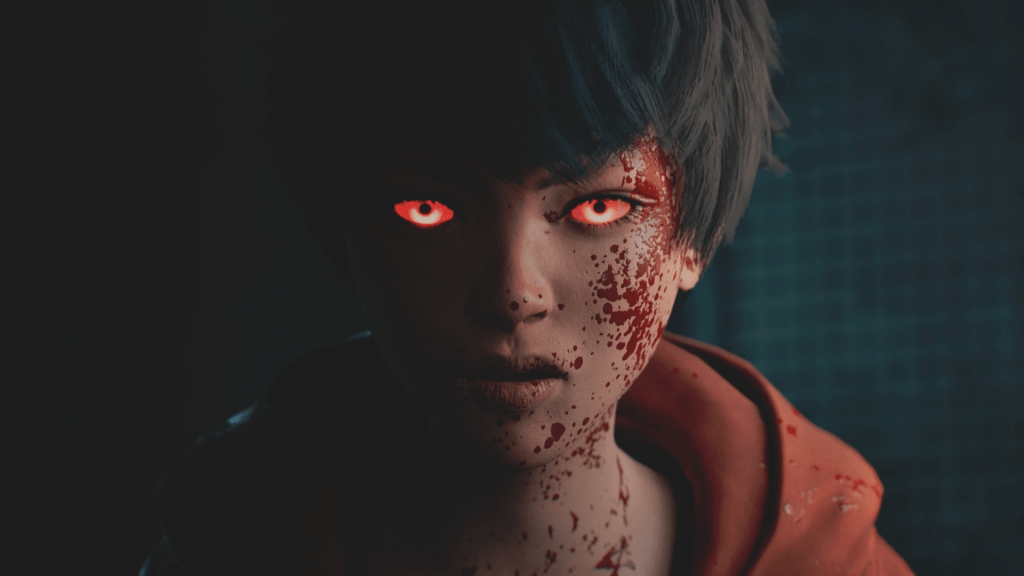

The story of Slitterhead has all the hallmark traits of a Toyama game, with the added flair of Yamaoka’s music to create a rather messy, but endlessly intriguing game. It feels larger than life thanks to its mind-bending elements of time travel and sci-fi concepts. Yet, it feels remarkably intimate at the same time. It’s a much more human story than you’d expect from a horror game, with all the characters sharing their hopes and dreams with Night Owl. It creates a personal connection with each Rarity, and feels like a genuine bond that forms throughout everyone’s experiences with the game. Because of this it feels all the more devastating when Alex’s vengeful drive starts to overwhelm Night Owl’s personality and completely overshadows the influence of the other characters. While people like Anita might be okay with the onslaught that follows this sequence, Julee most definitely is not, going as far as to leave the party and actively fight against the spirit.

This didn’t just leave a void from a gameplay perspective, but also felt like a complete loss of a part of the self. Something felt missing. Whether this was the intended sensation that Bokeh wished to create for its players, I don’t know, but it was shockingly effective. I felt frustrated, lost and driven to solve whatever damage Alex was doing, both to Night Owl and Julee. Toyama has managed to create similar feeling plotlines with Siren 1 and 2, but neither of those reached the levels of intimacy that Slitterhead provides. The closest analogy I can offer is visiting friends for the first time in a long time.

The grander scope of the narrative provides a nice balance to create a sense of urgency, as well as gives a lot of puzzle work for players to strong arm through. A lot of that has to do with the actual puzzle work you have to do to find all the plot details. Throughout the game you’ll encounter a strange script, which at first seems like the language that the monsters speak. However, through a few hints you can unravel the cipher by finding contextual hints. I went out of my way to completely decipher the alphabet used by the Slitterhead to decode a few of the Hyoki’s memories and it did unravel a lot of plot details that you can easily overlook. This part, especially, feels like a nod to Siren’s collaborative puzzle design. While it’s relatively easy to figure out once you know where to start on your own, it feels designed with groups in mind, with different players contributing to the solution so that the whole may understand the complete picture.

As much as I like to bash Siren for its convoluted design that didn’t translate too well to a culture that wasn’t as well connected at the time, it did provide the game with an extremely memorable personal investment. I’m extremely happy to see these types of designs return in Slitterhead! I do however find the execution of the narrative a bit messy, with the player being able to freely access any mission at any time. I get that this also adds to the time travel angle of the plot, but at the same time it manages to deflate any tension. To give one more Siren analysis; In Forbidden Siren there is a similar time cycle around which the plot is centered, the key difference being that, while the missions are freely accessible once unlocked, each puzzle piece serves as a means to progress the story forward. Slitterhead misses that element nearly entirely. It jumps back and forth between the different plot lines, and constantly introduces new elements, while leaving threads open. It would’ve served the game a lot better if you’d get locked into one major plot thread at a time, instead of juggling three. It’s by no means a bad story, in fact, it’s fantastic. You just have to sort out what mission belongs to what part of the narrative.

Horror as an action game

Slitterhead manages to use the horror elements of its narrative and flips it upside down into an action frenzy. The game is divided into various stages that you can select from the overworld menu, and these stages range from massive neighborhoods with a labyrinth of alleyways, to buildings latching into one another with concrete claws. When the plot doesn’t send you chasing down grotesque, insectoid monsters, you get to freely explore the surprisingly vertical landscape. It’s a downright addictive feeling to fly around the map and rummaging through every nook and cranny to find collectibles. Most of the game will have you take control of two Rarities in order to hunt down and kill Slitterheads in the area. Each Rarity brings unique abilities to the table and provide unique playing methods for each of them. My personal favorite is the team-up of Anita and Julee. Anita has the ability to summon people to any battlefield and cause them to go into a frenzy to attack the enemy. If you combine that with Julee’s more compassionate side of being able to keep people around you alive through blood healing, you’ve got yourself an infinite moshpit of disposable. Each character’s special moves also reflect a lot of their personality. Julee’s compassion translate to healing and supportive, while Anita’s abilities translate from a lifetime of poisonous manipulation to survive. Alex, likewise, has abilities that mimic his aggressive need for the destruction of the Slitterhead, with an arsenal of guns and the ability to turn people into living bombs.

Combat is a tug of war of parrying and striking between you and the enemy. Whenever you lock onto an enemy, their attacks will be telegraphed by a line around the direction the attack will come from. It’s up to you to time a flick of the right analog stick in this direction at the last second to parry a move. If you’re too early or too late you’ll get hit, but if you time it correctly it causes enemies to recoil, giving you an opportunity to inflict massive damage. You can also block incoming attacks, but this drains a blood meter. If that meter runs out, your weapon temporarily breaks and you get hit for a bit of extra damage. Most of the combat in Slitterhead turns into an almost rhythmic dance of death between you and your opponent. It’s incredibly rewarding to learn each enemies’ pattern and go from being backed into a corner to toying with them on auto-pilot. Alongside the attack, parry and evade dance, there’s also the possession mechanic that comes into play. You can freely swap between available bodies during combat, with the caveat being that if you die when possessing a body you lose a spirit point. If these run out, it’s game over. You’ll quickly learn to be aware of all the able minds around you to get the best point of attack on enemies. An added side effect is that whenever a Slitterhead winds up to attack someone, they will always finish that attack before figuring out that the Hyoki is no longer there. A lot of my strategy was to bait moves, then immediately possess someone behind it and keep playing this mental tennis until the Slitterhead was killed.

In between missions you can upgrade your Rarities’ weapon strength, abilities and passive abilities with skill points earned from completing missions and finding memories. The passives range from being able to re-attach severed limbs, to being able to parry multiple enemies at once (an incredibly useful skill for the late-game). You can also engage in conversation with the Rarities that joined you so far (including Blake, who just shows up wearing a Joker mask). Throughout these conversations you get to know the people that are working with you against the Slitterheads, but they also impart a part of their own personality to Night Owl. It can be interpreted that each character represents a dominant personality type that, when combined, make up the original personality of Night Owl. Throughout the game you’ll notice that whenever he talks to Julee, the spirit noticeably calms down, but when talking to Alex, the demeanor changes to aggressive and bitter. It’s a fantastic way to present your characters, but not as fantastic as the presentation of the dialogue. Each dialogue scene plays out with the characters superimposed on a background of their homes with the characters doing various things around the house. The entire presentation feels surreal, almost like your inner dialogue made tangible with hazes of color and light making the entire experience feel otherworldly.

The pitfalls

Despite this being a game that feels so intrinsically me, I do have a massive gripe with the way dialogue, or monologue, is writing and presented in the stages. For a game that loves to introduce intense chase sequences, it maybe loves deflating any tension that would’ve been present even more. Most of the text in Slitterhead is presented through a textbox that will interrupt the game and grind the pace to a halt. So, whenever you encounter anything in the game, a pile of corpses, street lights, a guy wearing rain boots on a sunny day, the game will toss any and all momentum aside to present you with a new text box. Each time a new bit of text gets introduced, you’ll freeze in place, only for Night Owl to state something completely obvious and instruct the player what to do next. This is fine for the earlier stages of the game, when players are still trying to get their bearings, but at a certain point you have to let the player make their own mistakes and let them figure out the logic behind your design. It’s similar to having a Dungeons and Dragons session, but each time the players talk amongst themselves the dungeon master interrupts with new exposition. Slitterhead, whether intentional or not, is written in a way that you’ll never be uncertain as to what the next step to progress actually is. So you can imagine that, when you’re in the thrill of the chase and body parts are flying all over the place as you rush after the monsters, only to be stopped by Night Owl to receive instructions on the exact thing you’re already doing, can lead to some frustrating momentum killers.

There is a part of me that theorized that this is intentional design. After the release of Forbidden Siren, most of the criticism was pointed in the incredibly obtuse methods of progression. A lot of that game was designed to be explored whilst players would communicate through message boards, which were highly popular in Japan at the time, but not so much in the west. The result was that the game got a lot of criticism for being heavily cryptic in how you’re meant to progress. After all it was a puzzle designed to be solved by more than one person, baton passing new bits of information along the track. I can’t help but feel as if the overreliance on simplified instructions given step-by-step, was a response to these critique’s. It could just as well be a miscalculation from the team. Regardless of whether my theory is true or not, it does detract a lot from what would otherwise be a very intense experience. It’s something that I feel could’ve been reworked with more voiced dialogue, like have the character you’re playing yell at Night Owl whilst running. This would’ve kept the effect of instructing players, but delivered it in naturally flowing dialogue that would emphasize the tension of these sequences (of which there are a lot).

A very specific game for a very specific audience

Slitterhead is definitely a game that will cater to a very specific audience. It’s not the most accessible game from a modern design point, despite being host to a few of the pitfalls that games from said modern era often fall into. It’s a game that oozes with a style that can only be described as if punk-rock got a healthy dose of vaporwave and then decided to make a horror game. It mixes deeply atmosphere moments with the incessant hum of overhead neon signs, only to break the silence with otherworldly, inhuman screams, and shredding guitars powered by the dirtiest distortion pedals. At the beginning of this review I mentioned the holes in Amigara Fault, and how this game was made for me. While it’s hard to describe why, each and every moment of this game felt catered to my tastes, to the most niche corners of my preferences.

The visual presentation provides impressive environmental designs that feel on par for the generation of consoles it released on, yet the character models look like a more polished Playstation 3 game with the animations of the Playstation 2. It gives the game a somewhat jarring look that I really appreciate, and really gives the game a unique visual identity. The dialogue sequences remind me a lot of Suda51’s Silver Case and The 25th Ward in it’s presentation, with the characters presented as transparent figures hovering through a haze of color. This alongside the extremely stylized loading screens alone made the game stand out for me. The music is incredible as well, with the game hopping between vaporwave, heavy metal, free form jazz and hip-hop influences. It gives the game a constant tonal whiplash, but somehow it feels like a cohesive whole.

These juxtapositions in tone don’t hold a candle to the absolutely mindboggling rollercoaster that is this game’s story. My initial expectations were more along the lines of a brooding murder investigation turned monster mayhem, but what we ended up getting both undermined those expectations and exceeded it by an immeasurable distance. Yes, we did get the brooding murder mystery for a whopping 20 minutes, but the game quickly introduces the core of it’s narrative with the ghostly time travelling and character drama’s. It tries to tell deeply personal tales against a convoluted backdrop of a bootstrap paradox, and somewhat succeeds at it.

The premise is somewhat undermined by the free selection of missions instead of a chronological approach, but this does give you the freedom to visit and revisit stages whenever you please. It’s a nice touch for a game that has so many clues hidden in plain sight, but it does undermine any sense of cohesive structure. One minute you’re facing a cult that turns people into brains with legs, the next you’re facing a time traveling parasite that keeps mocking one of the characters. It’s a bit of a mess that requires the player to take some initiative in sorting things out for themselves, and knowing Toyama’s previous works, that might’ve been the point. Alongside this is the fact that the game barely has any voice acting, and when it does, it’s about as confused about it as I was. Most of the voice lines are muffled grunts and noises of a similar caliber, but every once in a while a character will start juggling English, Japanese and Cantonese. Sometimes in the same conversation. I feel like this is one of the rare instances where either one or the other would’ve helped with a more cohesive tone throughout the game.

Overall though, Slitterhead provides a slick and stylish backdrop using the rarely seen Kowloon as its setting. The claustrophobic alleyways and encroaching high-rise buildings threatening to swallow up everything between its dark and shadowy walls add so much flair to this particular title. It’s a complicated game, that showcases both the best and worst traits of Toyama’s prior works. I am deeply in love with Slitterhead and its messy and convoluted design, but it’s a very specific balance of mechanics, design and presentation that made me fall head over heels with it. It certainly isn’t a game that will appeal to a mass audience, but, at the same time, it doesn’t have to. For a debut title from Bokeh Game Studio, it provides you with everything you need from a title created by two masters of horror.

Slitterhead is one of those games that does one specific thing for one specific audience type and I feel like we need more of this. It breaks the homogenized mold of spotlighted modern game design as an avant-garde experiment with a few different genres, seamlessly blended together into a brilliant concept executed with a good amount of flaws. I thrive on these kinds of games! There’s a lot of stuff I didn’t cover in this review that delve deeper into the narrative, but I did need to save some for a potential deep-dive video. If my enthusiasm during the writing of this review wasn’t enough to get you to give it a go, there’s a demo out that you can try. It’s a bit late to the party, but it will give you a chance to dive head first into the mystery of Slitterhead. And what a mystery it is!

Timetravel via microwave/10

TanookiChickenAttack is made possible by supporters on Ko-fi. If you enjoyed the review, consider becoming a supporter through https://ko-fi.com/tanookichickenattack